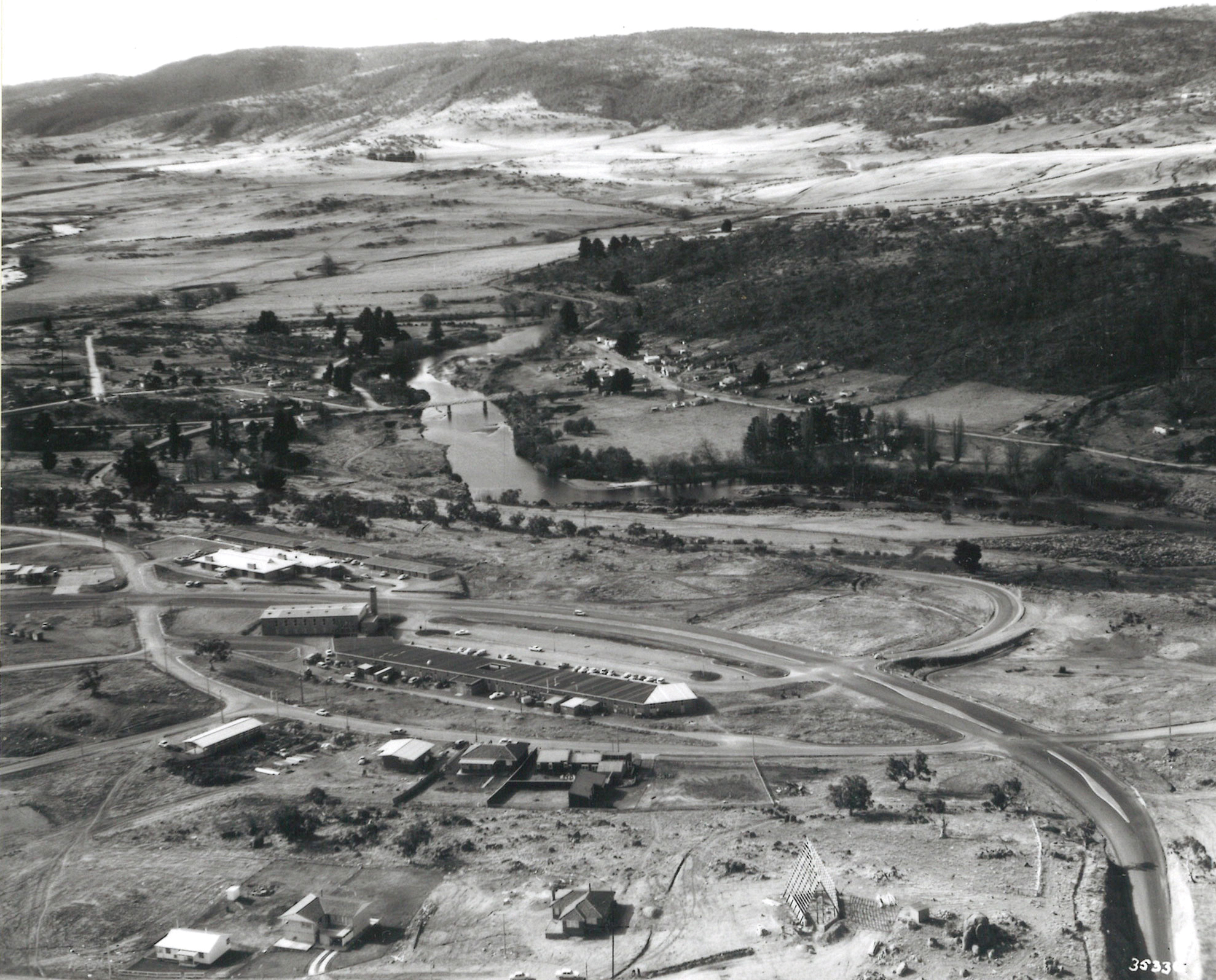

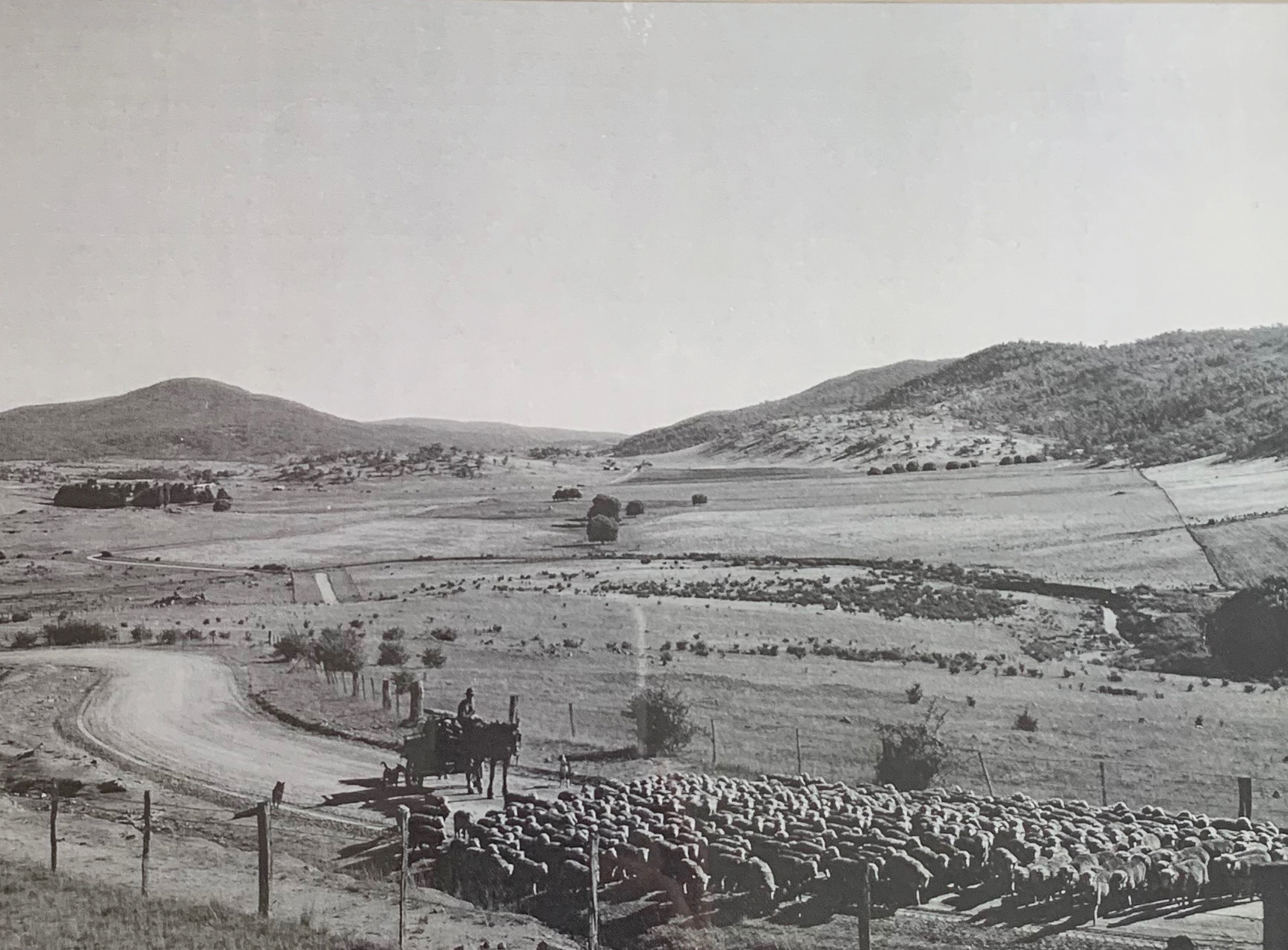

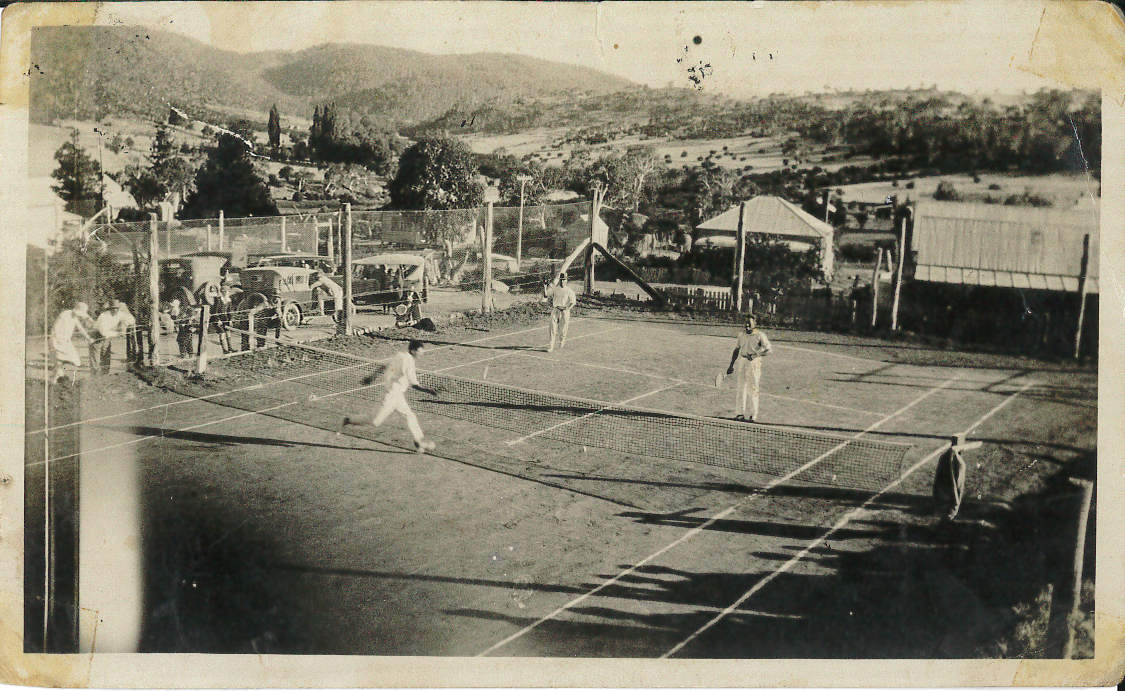

Before the hustle and bustle of a winter snow season or mountain biking and water sports in Summer, Jindabyne was a small country town with the mighty Snowy River snaking through the valley.

It is hard to believe that more than 50 years ago the small town of Jindabyne was relocated and the remnants of the old town flooded.

Fifty-six years later the history of Jindabyne is unforgettable as the town is brimming the edges of Lake Jindabyne, where the original town sat for many years before being flooded in the mid 1960s.

Old Jindabyne was flooded when the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Authority harnessed the waters of the Snowy River, as part of the Snowy Mountains Scheme. The scheme began the planning phase in the 1940s so it came as no surprise to locals that new construction was banned in the old township in late 1956. The goal of the scheme was to divert the Murrumbidgee, Snowy and Tumut Rivers in south western NSW to provide irrigation water for the western side of the Great Dividing Range, and in the process generate hydro-electric power. The Department of Local Government officially announced in 1960 that the town of Jindabyne would be relocated to its new elected spot where between 1962 and 1964 the town was re-established on the new site.

The Jindabyne Saga was held in April 1967 and was a wonderful pageant of old vehicles, pack horses, and a bullock team. Locals and visitors dressed in period costume crossed the bridge as Cora Byrne, descendant of Mrs McEvoy rode across the rising water of the Snowy River, a fitting memorial to times past. Three months later, June 1967, the historic bridge was blown up by the Army and the local school children were bought across to the area in front of the bowling club to see this historic event with teachers, parents and many interested citizens. Long standing local of Jindabyne, Greta Jones, remembers the historic day, saying “I don’t think we realised the enormity and long-term situation that was ahead.” The bridge is remembered as a symbol of the original town that connected the community to the surrounding region and recollections of the demolition of the bridge are still felt with sadness.

The main consideration in planning the new Jindabyne town was locating the main road in a position that would take advantage of the lake views. The new town of Jindabyne was planned to ensure the town had the opportunity to develop as an important centre for tourism as well as being a desirable township for residents. Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Authority moved the remains and headstones from the old cemetery along with the Memorial Gates and World War 1 plaques, with the original gates from the Presbyterian Church now in place at the Alpine Uniting Church. These items are some of the very few from the original town. The old town had disappeared and the new town was established, bringing with it a new era in the lives of many local residents.

The Snowy Scheme

In August of 1949 the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Authority launched the biggest construction project to be carried out in Australia in that era.

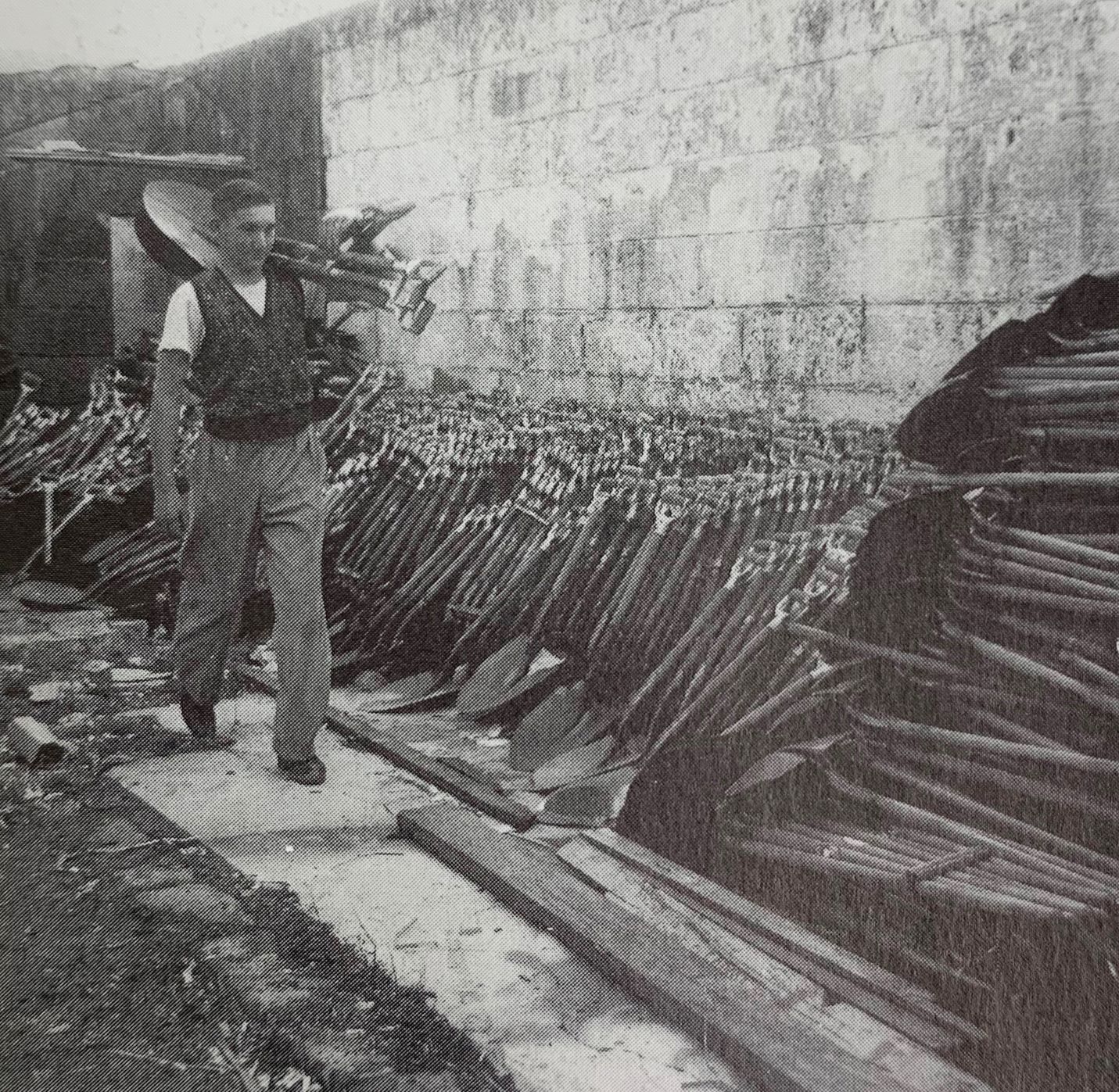

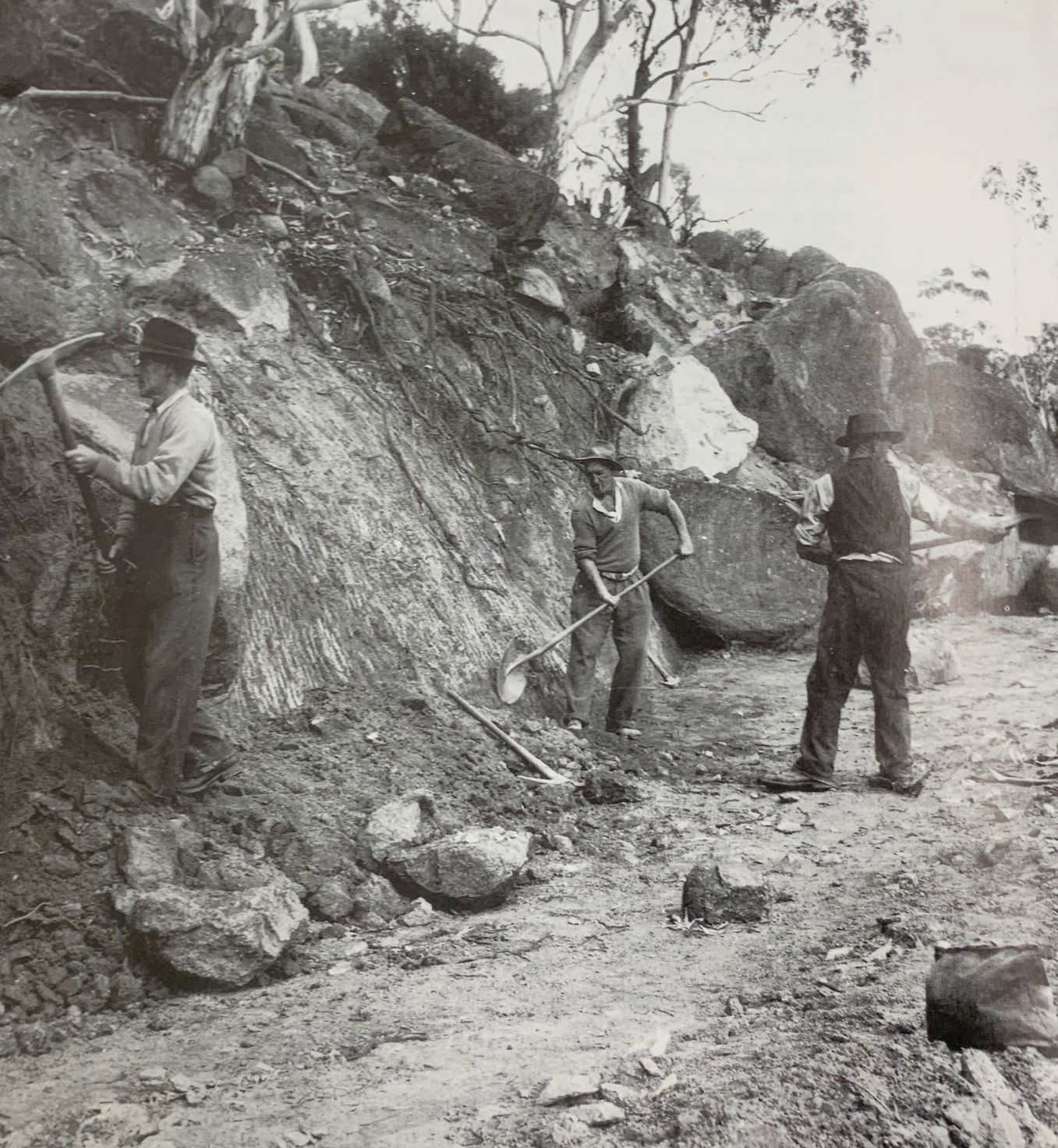

Nowadays we depend on heavy machinery to cut our pathways but a pick and a shovel was all that was available to cut an access track to the Number One dam site at Jindabyne. Shovels were about the only item that were not in short supply on the Snowy project in the early days of the scheme. There was a shortage of plant and equipment but the work went ahead, with workers digging trenches and shafts all by hand before later in the project being given tractors, bulldozers, angledozers and industrial diamond drill bits.

The project consisted of the diversion of the Snowy waters from their path to the sea. By means of tunnels under the Great Dividing Range, they would instead be channelled to flow into the Murrumbidgee and Murray Rivers and irrigate the dry inland. The scheme was envisaged as having two distinct sections: the Snowy-Tumut development, in the north of the mountains, and the Snowy-Murray development, to the south. The Snowy-Tumut development entailed the diversion of the Eucumbene River, the upper Murrumbidgee River, and the Tooma River, to the Tumut River. The rivers would be channelled westwards by means of tunnels, and eventually released into the Murray and Murrumbidgee valleys for irrigation. Their flow would be regulated by the provision of two main water storages in Jindabyne and Adaminaby dams.

In all, it was estimated that the Scheme would require the construction of about 145 kilometres of tunnel, 16 power stations with most to be underground, seven major dams that were up to 76 metres high and 800 kilometres of racelines to intercept subsidiary mountain streams, totalling a massive cost of $820 million. Through further investigation by the scheme leaders some modifications to the plans were made. Adaminaby dam, now known as Eucumbene dam would become bigger storage that would interlink the two sections.

The construction of the Snowy Mountains Scheme was seen as a means of supplementing the flow of the great inland rivers, a means for developing hydro-electric power and also a way to increase agricultural production in the Murray and Murrumbidgee valleys. Dams were built, tunnels were cut through the mountains, pipelines laid and power stations constructed.

It took 25 years to build, was completed in 1974 and is still the largest hydro-electric scheme in Australia. Far more than just an infrastructure project, more than 100,000 people from more than 30 countries were employed to work on the scheme. Each worker was envisioning a prosperous future by allowing the diversion of water to farms to feed a growing nation and to build power stations to generate electricity for homes and industries.

In 2019 the 70th anniversary of the scheme was celebrated in Adaminaby on the shore of what became Lake Eucumbene, with a tribute to past and present workers of the scheme many gathered in remembrance of the scheme that changed the methods of the power industry all around the world. This project would mark one of Australia’s most well-documented part of the nation’s history and a leading example of

Australian innovation.

The Old Town Emerges

Memories of yesteryear and town ruins are able to be seen and met with great interest when the water levels drop low enough to expose them.

Today, Jindabyne has grown and evolved in the many years since its relocation and the area has become a tourist mecca through both the winter and summer seasons. New suburbs, industrial estates, accommodation sites and much more have expanded in the once tiny town of Jindabyne to accommodate all who visit the area. As the town has grown and changed, new families have moved into the area but many old family names which were firmly planted here long before the Snowy Scheme have remained and witnessed the change.

Many long standing, well known families are still in the local area and tell their stories of their descendants growing up in the area before anyone knew it as it is today. The Pendergast family still resides in Jindabyne with Ian Pendergast remembering the story of his great great grandmother Mrs McEvoy, who was the first white woman to ride across the Snowies, along with many stories of a time before the Snowy Scheme existed. Tom Barry of Jindabyne is also a well-known name in town and is passionate about the areas history. Tom is currently working closely with the NSW Government to welcome a much-needed Historical Heritage Centre in Jindabyne so the stories and history of the area can be preserved and shared with everyone.

Parts of the Old Jindabyne town can be seen when the levels of Lake Jindabyne are low, particularly the foundations of the old St Columbkille Roman Catholic Church. Lake levels have reached an extreme low at present and the foundations of the Church have appeared, along with

several chimney stacks and other remnants of what was once the town of Jindabyne.

Much of Jindabyne’s history has been documented in many publications though there is not a central location where its entire history is mapped out for all to see. Jindabyne has many extraordinary and dedicated members of the local community committed to telling and preserving the history of Jindabyne. “It is important that we acknowledge and emphasise the diversity and significance of the Jindabyne area as a social

and cultural landscape”, Mr Barry said “An Historical Heritage Centre in Jindabyne will allow for visitors and locals to see how this amazing area came to be.”

The National Parks and Wildlife Services Information Centre has a diorama located in the foyer of the building displaying the old Jindabyne township, a special feature for the residents who once lived there. The diorama was the brain child of Jimmy James and was put in place when 40 years of the new town was celebrated. Jimmy passed away a short time later and left a lasting and loved legacy of historical value for others to reflect upon and enjoy.

The Snowpost would like to thank the following for contributing their knowledge and images to this feature story on Old Jindabyne: Tom Barry, Greta Jones, Ian Pendergast and Snowy Hydro

For more articles and information on the region head to www.monaropost.com.au.