With a population of little more than 300, you’d be forgiven for not realising the small town of Adaminaby has a history intertwined with the spirit of the nation.

It has been home to members of the Ngarigo nation prior to white settlement and a supply stop for prospectors heading to the Kiandra goldfields. It has been ground zero for Australia’s largest engineering undertaking, seeing the first blast of the mighty Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme on October 17, 1949.

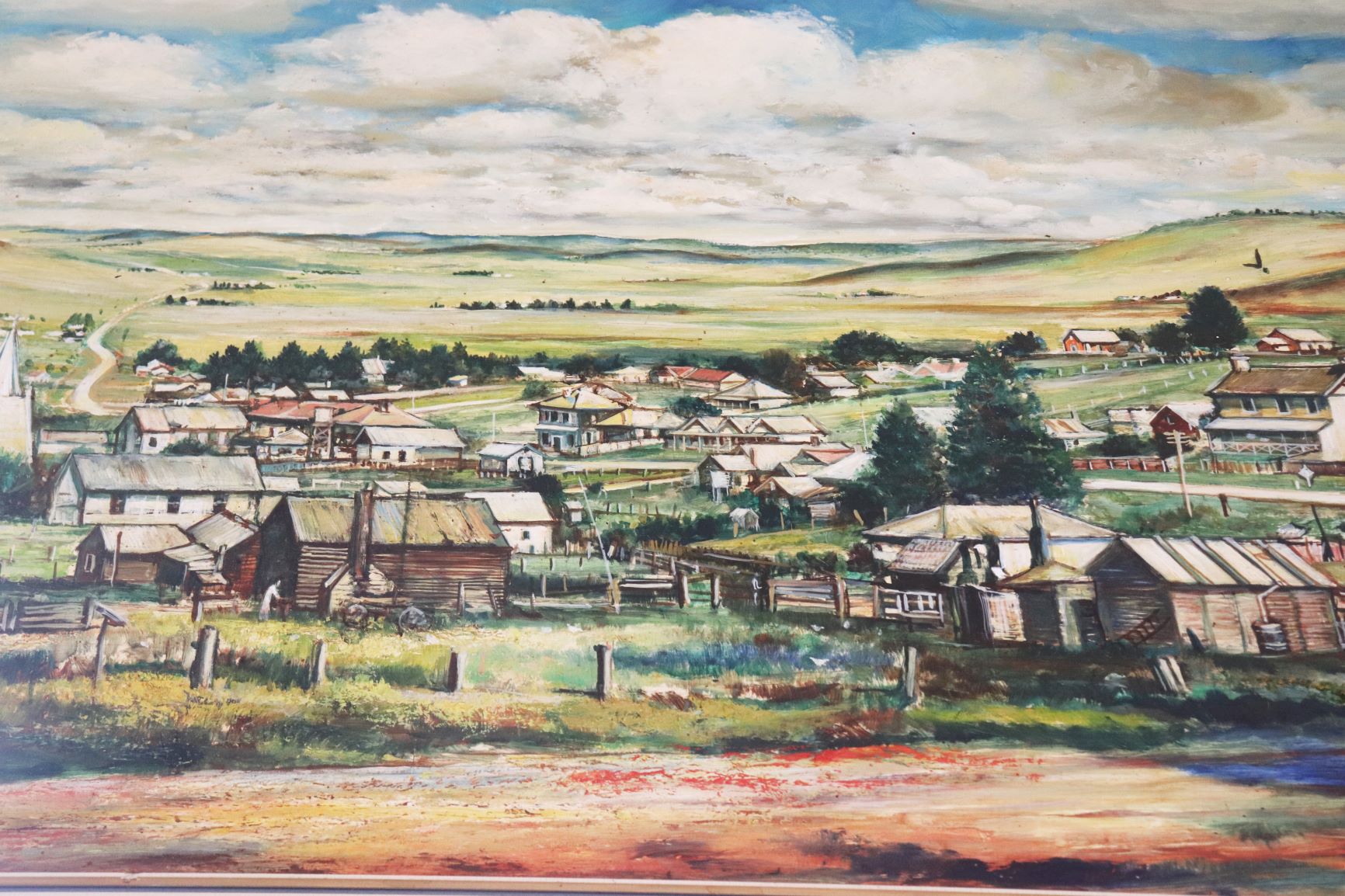

The town was the first in Australia to have been moved, in some cases, brick by brick, to make way for Australia’s greatest engineering feat to date. The result, locally, has been a mecca for trout fishermen and a gateway to exciting Snowy Mountains adventures. Adaminaby has provided inspiration to our most beloved poets and authors and even been the setting for a number of movies. The region is also rich in farming and grazing history.

Now, more than a century since the area was first settled by Europeans and more than 70 years since the beginnings of the scheme that would put it on the map, we’re taking a look at the proud history of Adaminaby, to see there’s more to this small town than meets the eye.

Indigenous History

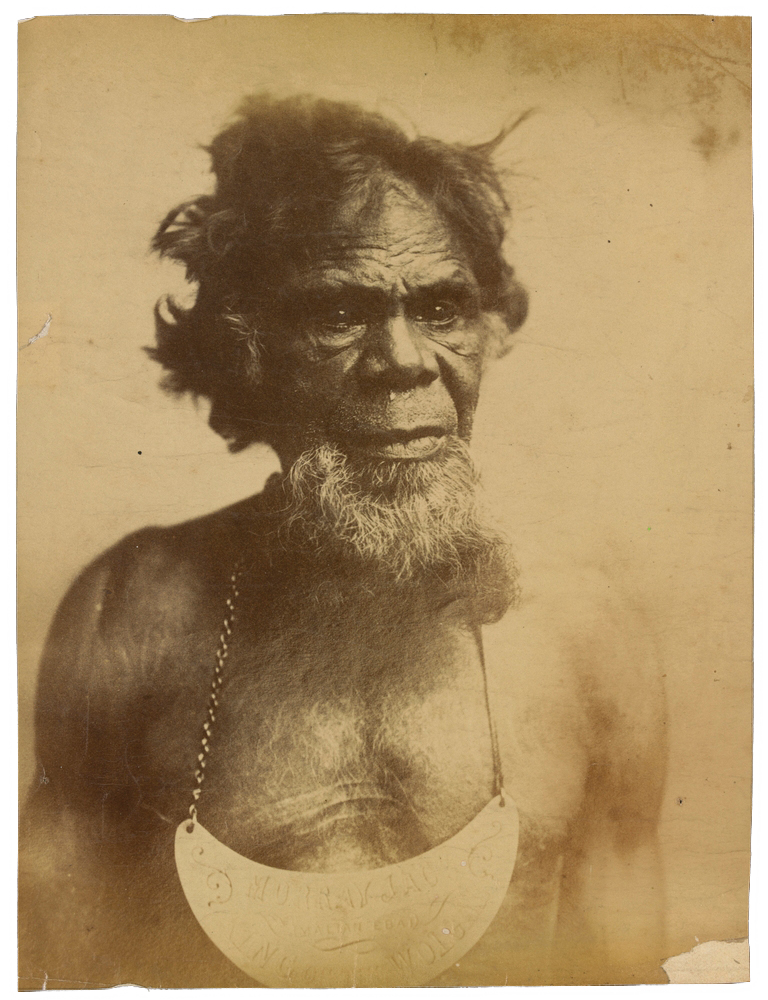

Tens of millennia before Europeans first stepped foot in the area, the region was home to the Ngarigo people, who occupied the country between the southern reaches of Canberra to just south of the NSW/VIC border.

The Ngarigo tribe is made of a number of different clans, each claiming rights and responsibilities to a particular part of the region.

The Bemerangal had responsibility for the area which now includes the towns and villages of Adaminaby, Bredbo, Numeralla, Cooma and Jindabyne. The Bemerangal travelled seasonally between the Monaro and the South Coast along traditional travel routes which took them along the Tuross River to Bodalla. In the Summer time, many tribes would travel to the mountains and meet for special ceremonies including the feasting of the Bogong Moth, an event for which thousands would gather.

The arrival of European settlement saw much of the local indigenous population killed by disease and violence. Some of those that survived worked on local properties to maintain a connection with their country. Others were relocated or forced into Aboriginal reserves. Consequently, much of the Ngarigo culture and language has been lost. There are still however, a number of proud Ngarigo men and women working to keep it alive.

Early settlement and gold rush

The first settlers to the area were farmers, establishing a number of properties along the Eucumbene River from the late 1820’s. These early settlers included Charles York and Henry Cosgrove, who in 1848, applied for the 6,730 hectare “Adumindumee” run at what is now the site of the old town.

The population in the region increased dramatically when gold was discovered in November 1859 and the resulting goldrush drew in people from around the world. It established the gold-mining town of Kiandra that would also become the birthplace of Australian snowsports.

The small hamlet on the banks of the Eucumbene River called “Chalkers Hamlet” had become a staging outpost for those headed to the Kiandra goldfields. Before long, a hotel, post office and some stores were established. In 1861, the village was officially surveyed and noted by the NSW Government, to be named “Seymour” after the maiden-name of the surveyor’s wife. Sparked by the goldrush, the population of Seymour

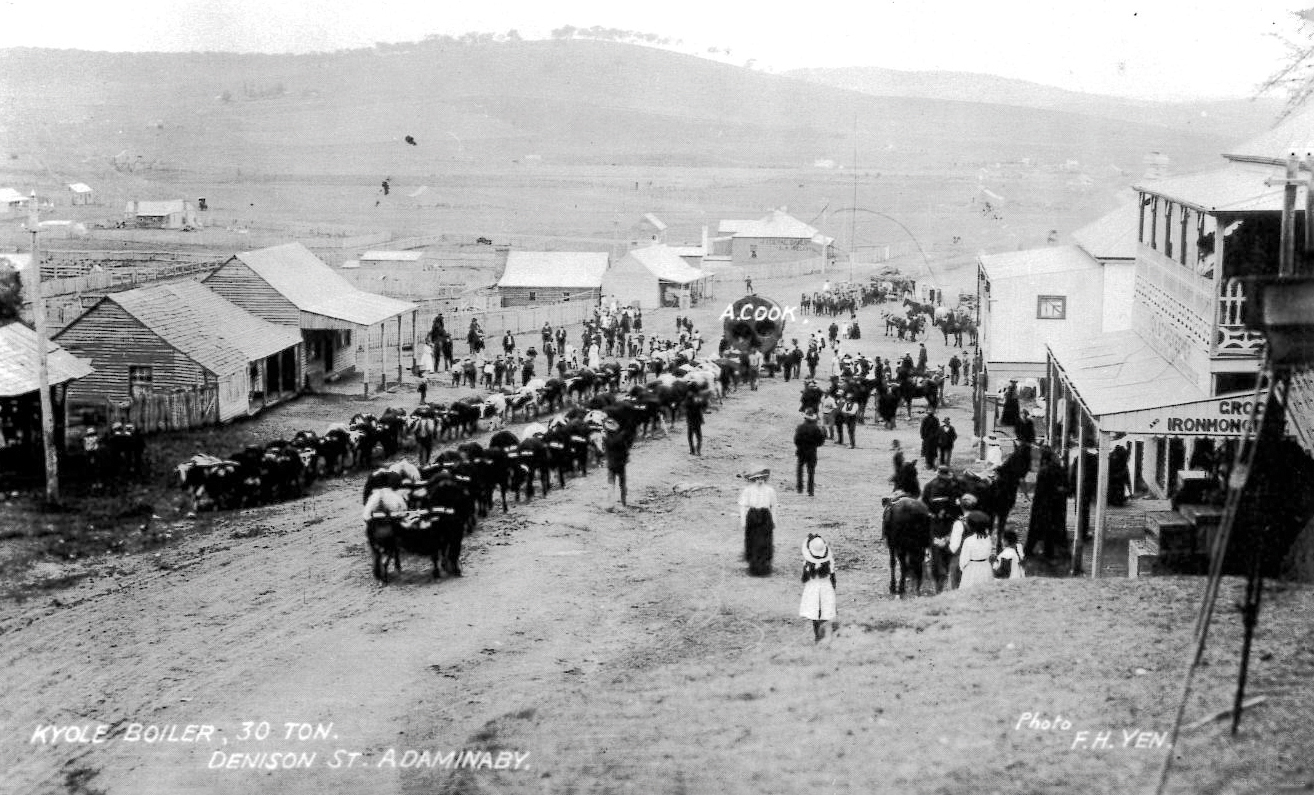

continued to grow and by 1877, supported 400 residents, three stores and three hotels. Due to some confusion with the Victorian town of Seymour, it was later decided that the town’s name should be changed, and in 1886 it officially became known as Adaminaby.

Mining operations at Kiandra ceased in 1905, after 48,676kg of gold had been extracted, but by this time Adaminaby was already a well-established regional town. In the late 19th century, copper was discovered at Kyloe and in 1901, the owners, Litchfield and Hassal extracted nearly 30 tonnes of copper, worth more than $1 million at today’s prices. The Kyloe Copper Mine contributed significantly to the town’s economy. At the height of production, it employed 195 men and boys and turned out copper until it was worked out and abandoned in 1913.

By the 1920s Adaminaby could boast a watchmaker, cafes and tea rooms, a cabinet maker, a local paper, a hospital, a doctor, two schools, a showground and a racecourse. The population during the 1940s was 750, although the town also provided for hundreds of people living in the nearby rural areas. However, life in the town of Adaminaby was about to be changed forever, as it found itself at the epicentre of the largest engineering undertaking in Australian history.

The Snowy Scheme and relocation

Taking advantage of snowmelt and diverting the mountain rivers to create water reserves had been a long- held ambition of local landowners since the mid 19th century, as they came to grips with the dryness of the country. Power shortages in the First World War had also led to the proposal of using the Snowy River’s fast flowing water to generate hydro-electricity.

The final proposal was for a scheme that would provide both water storage and electricity, and in 1949, the Commonwealth Government passed the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Power Act, beginning the world’s greatest engineering feat of the time.

On October 17, 1949, an opening ceremony was held in Adaminaby and attended by Sir William Hudson, the Governor General Sir William McKell, and the Prime Minister Sir Ben Chifley, alongside other dignitaries. A ceremonial plaque was erected, and the Governor General plunged the detonator on the first explosive blast for the first and largest of the scheme’s 16 dams, the Eucumbene Dam.

The initial proposal for the Eucumbene Dam wall location would see the waters rise to just below Adaminaby, resulting in it becoming a lakeside town much like Jindabyne. However, after further investigations, a second site six kilometres downstream was decided on due to increased water storage capacity. The change meant that 24,500 hectares of the Eucumbene Valley and Adaminaby Plain would be flooded including a significant portion of the town itself. The plaque unveiled by the Governor General and Prime Minister would be submerged beneath several metres of water.

The town of Adaminaby would need to be relocated. This was a tough sell for the Snowy Mountains Authority, who were treated with suspicion by many locals.

Much of the land to be flooded was prime grazing land producing quality livestock. Graziers from around Adaminaby and Jindabyne formed the Graziers Protection Association, seeking legal advice. Aware of the sensitivity of the matter and keen to avoid litigation, the Authority settled on generous compensation and various options for displaced residents and graziers. Residents had the option of transporting their home to the new location – roughly five miles to the north-east – at the expense of the Authority or moving into a new house provided by the Authority or being compensated to the market value of their home if they wanted to move elsewhere.

Relocations began in 1956, and within 18 months, 102 buildings and two stone churches had been moved to the new town. Only four buildings were able to remain, being situated above the new high-water mark, where they remain to this day. However, many historic Victorian-era buildings, homesteads and artefacts were lost, and little effort was made to record the town before it was destroyed.

Many residents felt a resentment at the destruction of homes and properties that persists to this day, but the wheels were set in motion and the advancing tide could not be stopped. What was once the town of Adaminaby would forever after be known as Old Adaminaby.

Owing the nature of its existence to the scheme for better or worse, life in the new town of Adaminaby continued to revolve heavily around the scheme through to the end of its construction in 1974. However, as the Snowy scheme slowed down, another industry began to take root and flourish around the banks of Lake Eucumbene. Tourism.

Present day and legacy

The introduction of trout to the waters of the Snowy Mountains and the work of acclimatisation societies created one of the best trout fisheries in the world, drawing in anglers from far and wide. Adaminaby and Lake Eucumbene were and are at the centre of the scene.

The lake is also popular for boating and water sports. The birth of skiing at Kiandra evolved into Australia’s first ski resort at a nearby slope now known as Selwyn Snow Resort. While the resort was tragically destroyed in the summer bushfires, the rebuilding is well underway and Adaminaby will continue to be the staging point for those headed up the slopes.

The town has also inspired some of the nation’s greatest voices. While a matter of some debate, there are many who believe that the subject of Banjo Paterson’s iconic poem the Man from Snowy River was none other than famed Adaminaby Stockman Charlie McKeahnie. Others believe the character was a composite based on various people involved in the brumby hunts that were common across the region.

The only Australian to ever win the Nobel Prize for Fiction, Patrick White, spent two years working as a stockman at the Bolaro Station in order to improve his health. Finding he was not cut out for the life, he did however find the inspiration for his book Happy Valley, which was based entirely off his time there.

In 1959, film stars, Robert Mitchum, Deborah Kerr, Peter Ustinov, Chips Rafferty, John Meillon and more were seen at Adaminaby along with other towns in the region for the production of the iconic film ‘The Sundowners’. The 1980s film ‘Phar Lap’ was also centred at Adaminaby, where the Mexican Agua Caliente Racecourse scenes were filmed at the racecourse. A plywood grandstand was erected for the purpose and locals employed as eager movie extras.

Today, Adaminaby has a population of only 300, a fraction of what it has been in days gone by. It still, however, has the same sense of magic, wilderness and quintessential Australian Spirit that has provided inspiration to the nation.

If you liked this and were after more stories and information on the region head to www.monaropost.com.au